Think the US job market is healthy again? Well, it isnft

— and hasnft been for a long time

James Pethokoukis

July 9, 2014, 1:31 pm - American Enterprise Institute

Itfs not enough for an economy to generate jobs. There should also be a good

amount of turnover in the labor market. Workers need to move around to find the

best fit for themselves, not to mention higher pay from taking a new gig. A

stay-put workforce is bad news.

Now net job growth is a product of total hiring minus total separations

(including layoffs and quits), as measured by the Job Openings and Labor

Turnover Survey. And as a Goldman Sachs memo points out, ga given level of net

employment growth can be achieved with a high or a low level of gross

turnover.h

So long as there is decent net growth, should we really care how it comes

about? After all, as JPMorgan point out, the 231,000 average monthly job

gains in the first half of the year was the best of any six-month period in this

expansion. Actually, we probably should care about these job market

internals. Goldman cites two reasons:

– The first is that a less dynamic labor market is likely to see weaker

wage growth as workers fail to move to jobs in which they are more productive.

Fed research suggests that the impact on aggregate productivity growth could

be considerable.

– The second reason for concern is that a low-turnover labor market risks

locking out the unemployed and marginally attached, in some cases permanently.

This ghysteresish effect is a second channel through which a lack of dynamism

can reduce potential output.

More stasis means lower wages, less productivity, and higher long-term

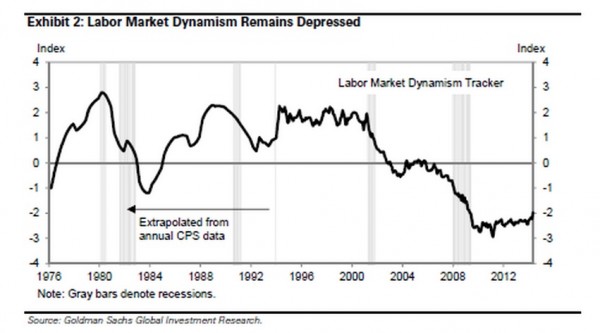

joblessness. So is labor market dynamism or churn declining? Goldman thinks it

is. The firm created a measure based on (a) the sum of the hiring and

separations rates in the JOLTS data; (b) the sum of the gross job gain and job

loss rates in the Business Employment Dynamics data; and (c) the share of

workers making job-to-job transitions in the monthly Current Population Survey

(CPS, also known as the household survey) micro data. Goldman finds:

c labor market dynamism has fallen substantially since 2000, with

the decline occurring during and after the last two recessions. Our

dynamism tracker has bounced back only weakly during the last two recoveries,

in contrast to the much stronger bounce-back following the recessions of the

early 1980s and 1990s.

Why the decline? There certainly may be structural reasons. Companies may be

imparting specific skills that donft easily transfer to other firms. The decline in new firms creation may also reduce worker

movement. But Goldman mostly blames weak economic growth. Insecure workers

are less likely to take a risk on a new job. As I have noted before,

it used to be common for the US economy to post a quarter of 4% or faster

real GDP growth. In the 1980s (1981-1990), there were 18 such quarters. In the

1990s (1991-2000), another 18 quarters. But in the 53 quarters since then, the

US economy has generated only six three-month periods of 4% real GDP growth or

faster, including just two during the Not-So-Great Recovery.

This is one reason Fed Chairman Janet Yellen includes

hiring and quits rates in her gdashboardh of labor market indicators. It also why the Fed should focus on growth right

now.